NAVIGATION

Navigating Navigation

Adrian Wojcik

Isabelle Diagne

Katrina Bžalava

Sophie Woodcock

In “Navigating Navigation”, Bzalava, Diagne, Wojcik, and Woodcock form a response to Van der Tuin and Verhoeff’s entry on “Navigation” in Critical Concepts for the Creative Humanities (2022) from four different disciplines. The essay explores how Navigation is seen, applied, and can be useful in the fields of Linguistics, History, Literature, and Media and Culture. By looking at maps not as a tool for navigation, but rather as a product, this essay explores the relationship between the opportunities generated through navigating, as well as the hindrances one might encounter when using the term in a creative setting. In short, the essay highlights the subjectivity and creativity that Navigation can generate.

In Critical Concepts for the Creative Humanities, Iris Van Der Tuin and Nanna Verhoeff evaluate and reflect on the term navigation with the intention of providing a clear characterization of all the processes navigation encapsulates within a creative context. Yet, scholarship can recognize that whilst forming a response to said definition, there inevitably will be a “yes and” consensus that manifests in detail. Therefore, this essay aims to expand upon such notions and apply multidisciplinarity as a means of critical evaluation.

Navigation, while etymologically holding a very precise application, has come to be related to many different fields. Stemming from the Latin words navis, which could mean “ship”, “through the sea” or “constellation”, and ago, or “to go”, (Dizionario Latino 2024) navigation is “the art of conducting a vessel from one place on the earth’s surface to another by sea” (Kemp 1988, 577). However direct this definition seems to be, navigation, in today’s world, can mean anything from traveling from one place on the earth’s surface to another, to learning a new concept, or even reading a book. Van Der Tuin and Verhoeff provide a broader definition of the term, namely that “[n]avigation is the process and method of wayfinding and steering of bodies, perceptions, or thoughts within a given or generative terrain, field, or domain” (Van der Tuin and Verhoeff 2022, 137).

Given this, the following essay is an attempt to draw forms of navigation and apply them to creative concepts such as decolonizing mapping practices, the mathematical properties of fractal art, and music composition. The concepts represent how navigation is applied in creative practice and illustrates how the term is exemplified in connection with various creative mediums. This essay will explore the relationship between the interfaces generated through the act of navigating, and the problem of prescriptiveness as a hindrance to the creative aspect of navigation. These interfaces, or maps, rather than being a prerequisite in regards to the act of navigation, should be taken as a possible, generated product or tool instead of a set of prescriptive rules to abide by.

Prior to applying navigation in a broader, more creative sense, it ought to first be defined and examined within its original sphere of influence. Navigation is a prerequisite for seafaring with purpose as it “invokes a spatiotemporal logic” and is “prospectively planned, structured, purpose-full, and goal-driven” (Van Der Tuin and Verhoeff 2022, 137). To plan a route from one part of the world to another, the navigator must not only be able to position the two locations in relation to one another, but must also accurately identify the location of the vessel during the voyage to steer the correct course. Throughout the varied histories of seafaring across the globe, there have been many ways that people have navigated the seas. The navigational practices of the indigenous populations of Polynesia and North America (amongst others) relied more on personal knowledge of nature and the seasons as opposed to Western seafaring, which has since the Middle Ages relied heavily on technology and tools of science (Genz et al. 2009, 234). Like many fields and disciplines, navigation is perceived predominantly within a Western context. Cartography is seen as an intrinsic, unmissable product of navigation, and yet this is not the case for all navigational practices across the globe. Instead, cartography is primarily a Western practice (Kemp, 1988, 143). Many other peoples were able to perform phenomenal feats of navigation that the Early Modern Europeans would have had no hope to replicate (Genz et al. 2009, 237). Nevertheless, cartography has become highly inseparable from the concept of navigation. Even when navigation is used outside of its original context of seafaring, cartography seems to come along for the ride. In Critical Concepts for the Creative Humanities’ entry on navigation, this too is the case; it is mentioned that “navigation entails the production of a performative cartography of a terrain, field, or domain that is constituted in the very act of its exploration” (Van der Tuin and Verhoef 2022 137), thus inextricably linking cartography and navigation in a likely unintentional western bias.

Advancements in technology, such as radio beacons in the 1920s, satellite navigation in the 1960s, and the introduction of Global Positioning System (GPS) in the 1970s, have vastly improved the accuracy and increased the speed by which a course can be plotted (Constantine 2008, 3). According to Master Mariner Philip Woodcock, this increased accuracy and optimization combined with more and more safety and environmental regulations has significantly decreased the creativity afforded to the navigator. In areas of high traffic, such as the English Channel, there are the “equivalent of motor ways in the sea …to prevent vessels from running into each other” (Woodcock 2023). However, this heightened level of restriction has also opened up new creative options within navigation. To reduce fuel expenditure, certain vessels have returned to using sailing routes with advantageous currents, exemplifying the idea that “embodied interaction is about the relationship between action and meaning, and the concept of practice that unites the two” (Dourish 2001, 206). Much like the constantly shifting currents of the world’s oceans, the creativity afforded to the art of navigation changes and shifts with each new advancement in technology or policy. Despite navigation happening in generative fields (Van Der Tuin and Verhoeff 2022, 137), there are intrinsic empirical constraints that shape and differentiate them that may limit creativity.

Preceding the exploration of the creative aspects of navigation, disciplinary perspectives within humanities will be compared in order to evaluate the applicability of Van der Tuin and Verhoeff’s critical concept of navigation. First of all, navigation can be applied to media and culture studies to describe the methods in which users interact and respond to the various mediated forms of communication that society now employs every day. The main disciplinary definition of navigation stands as “not only the behavioral actions of movement (e.g.,linking one information node to another) but also elements of cognitive ability (e.g., determining and monitoring path trajectory, comprehension, and goal orientation)”(Lawless et al, 2007). Navigation within media studies can be distinguished by the role it takes in making tangible products/platforms that foresee and predict how people will interact and utilize the platform itself and by using these techniques to organize and prioritize a medium’s information access and functionality. For example, word filters/catchers are an available option on various platforms to anticipate how users can avoid verbal harassment or online threats. Navigation then becomes a question of interaction between medium users and the actual interface, be it an application, website, gaming controllers etc. In this specific discipline, it encompasses how social platforms may use forms such as chronological order, wireframes, and general promoted content to help creators aid in understanding the needs, preferences, and behaviors of their users, and to make the medium function accordingly for the smoothest and safest use. Der Tuin and Verhoeff’s definition states “As such, “navigability” is not only a property of the domains, (hyper)texts, or interfaces themselves. “Navigation-ability” also requires skills and knowledge (or literacy) on the part of the navigator (or user-slash-participant)” (Van Der Tuin and Verhoeff 2022, 137), . With this additional quote from the book, the provided explanation for the concept is in alignment with the disciplinary definition as they both acknowledge the importance of the platform’s manipulation of the interface. Media studies embody the book’s definition whilst other disciplines have further interpretations.

Secondly, the concept of navigation manifests in literary studies through fundamental tools such as narration. At the core of literary navigation is a term coined by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, namely – the willing suspension of disbelief, implying the “transfer from our inward nature a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for [the] shadows of imagination (1907, chapter 14). For the phenomenon to take place, one must abide by the rules of the author and accept an invitation for interpretation. Only after the pact is forged and accepted does the factual navigation begin.

Immediately upon embarking on the journey, the roles are distributed – the narrator becomes the guide, and the consumer becomes the navigator. A narrator can provide multiple clues on the journey, meant to sway the reader, such as literary devices, contrasting use of language, even the persona of the narrator, formed by key indicators such as visibility, reliability, and involvement. The agency of the reader in interpretation is the catalyst for the “reciprocity and iterative loops between action, experience, and knowledge” (Van der Tuin and Verhoeff 2022, 138). Therefore, the consumer is the ultimate authority deciphering a text and navigating the narrator’s mind. Additionally, navigation may not be linear and chronological, and can take many forms. The consumer may decide to read a text in their desired order disregarding any guidelines and achieve an original destination that of the author’s intention. Rather than directions the narrator provides suggestions, making the reader the agent of navigation.

In regards to the discipline of history, navigation is regarded with distrust and only begrudgingly applied when necessary. History as a whole is too large and varied to be understood in its entirety without placing limitations on it or by framing it in a certain way, and yet doing so can cause significant distortions. Historians can dedicate their entire lives to studying the past, only to become specialists in one tiny facet of history. Then there is the debate on where the boundaries of history even lie. Supporters of Big History argue that history does in fact not begin in 3000 BC with the invention of writing, but instead ought to be traced back to the Big Bang (Hesketh 2014, 172). Regardless of when it is determined to begin, since the start of its discipline history has been divided into periods and sub-disciplines to make its study more comprehensible. While this certainly makes history more accessible, it does enhance the risk of distorting the past to make it fit within the plotted course. As Van der Tuin and Verhoeff mention, navigation is “destination oriented” (2022, 137) and if applied suggesting a narrativity and linearity in history that modern scholars are desperate to avoid. And yet for practical reasons it is nigh impossible to avoid distorting history in one way or another. Thus any sort of navigation of history can be qualified as a wicked problem.

The main instrument used to navigate the field of social interaction is language. Not only do human beings use it to convey their thoughts through words, but the manner in which one speaks can give insight on many features of the speaker: age and gender are some obvious examples, but finer details may also indicate factors such as the affiliation to a particular social circle or ethnic identity. The concept of prestige refers to the desirability and status that a linguistic feature has (Meyerhoff 2019, 43), and its presence leads to a paradigm where the desirable variant is also “good”: “he said” is generally considered preferable to “he was like”. From here, it follows that a speaker of a desirable variant is a “good” speaker. Such thinking is reflected in the discriminatory behavior towards language variants, such as African American Vernacular English being seen as ungrammatical while possessing well-formed grammatical rules (Meyerhoff 2019, 75). A more truthful representation of language as an instrument of social navigation arises when reversing the relationship between speech and belonging. Through the process of attunement, the tendency to either match or diverge from another speaker’s language when engaged in a conversation (Meyerhoff 2019, 57), speakers are endowed with the agency of being able to produce both closeness and distance between each other, and thus produce their social networks.

In a statement by digital artist Julius Horsthuis he defines his works (Picture 1), a collection of three-dimensional fractal art, as akin to a documentary: in the production of his renderings, he navigates “digital realms”.

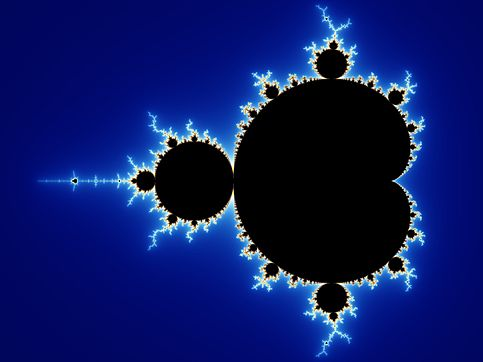

In an active process of navigation of such fields, Julius has the agency to choose “what to show and what not to show” in order to trace distinctive paths in an exotic graph. Fractals, such as the well known Mandelbrot set (Picture 2), owe their popularity to the fact that they are self-similar, meaning that by increasing the scale, or “zooming in”, repeated iterations of the original shape can be seen (Lei 1990).

Surprisingly, the topic of fractals is closely related to the issue of representing physical spaces. Consider the counterintuitive nature of length, on which Mandelbrot himself worked on, (Mandelbrot, B 1967) in this example: depending on the resolution, or unit of measure used, Britain’s coastline can be increased or decreased arbitrarily (Picture 3).

Jiang and Brandt, in an attempt to mitigate the impact of this effect, (Jiang, Bin, and S. Anders Brandt 2016) note the dissonance between the Euclidean paradigm, in which everything has an absolute measure, and the fractal nature of geographical expressions: the area and length of islands, coastlines, natural slopes are all dependent on the scale used. In the same manner as Julius’ fractal art, producing any kind of map involves a creative choice led by the needs of navigation: what to show, and where to zoom in.

An additional example takes place in cartography practices itself, since navigation exhibits various contemporary connotations, and implies much duality in its nature. On one plane of scholarship, the term offers opportunities to broaden and revisit research, on the other hand, navigation enforces harmful principles, many of which are rooted in hegemonic colonial power. The traditional practice of navigation has long been dominated and overshadowed by settlers and colonizers, nevertheless, modern research provides many tools in aiding the decolonization of indigenous territories.

A group of scholars from Canada launched a scheme, namely, the Indigenous Mapping Collective. On their website they state that the goal of the project was to “build a conference that gave Indigenous peoples direct access to the tools and training they need to map their lands”. By “supporting Indigenous rights and interests, decolonizing place and space, and sharing Indigenous stories of the land” (Indigenous Maps n.d), the project manifests in reclaiming the territories of indigenous communities and deconstructing monuments of colonial authority. Decolonizing the maps “seeks to reclaim place-based, ancestral, Indigenous knowledge while also enacting the contemporary world-making practices of Indigenous and colonized peoples in the present” (Rose-Redwood et. al. 2020, 152).

Such a project is crucial in navigation research for a plethora of reasons. For once, it is highlighting the ancient traditions of mapping practices and the knowledge of the land and creativity displayed by the tribes. Additionally, it emphasizes the gravity of narration and discourse. In combination with graphic tools, narration implements semantic value to the representation of a graphical space (Drucker 2008, 123), and restores the status of indigenous voices. An additional project, namely The Decolonial Atlas, meant to challenge the belief of cartography being objective, provides further inquiries on the decolonization of navigation and maps.

Finally, the last creative practice worth mentioning concerning the term navigation, is music, more specifically music composition. In an interview with Maurice Horsthuis, a classically trained violinist, he says “without a navigation system, a ship on the ocean cannot see where it is. Instead, an artist starts in the middle of the ocean: a blank sheet of drawing- writing- music paper, or a large blank canvas on the easel, and finds his way” (Horsthuis 2023). With this in mind, music composition has several linkages to navigation. For example, melodic navigation in itself, (using melodic intervals to create motifs that guide the listener’s attention through a song) is a way in which artist and listener connect to maneuver around common orchestrations of music genres. Mireille Besson and Daniele Schön indicate that within music, one classically differentiates the temporal (meter and rhythm), melodic (contour, pitch, and interval), and harmonic (chords) aspects. They explain that each aspect requires different types of processing and navigation of melody and harmony within a piece so that the composer can articulate a musical message or evoke a specific response from the listener (Besson and Schön 2001). Additionally, rhythmic manipulation within music creation is arguably a form of navigation taking place in creative practice. Aniruddh Patel and John Iverson state that “While much popular music is composed in such a way as to guide the listeners’ beat perception (e.g., by physically accenting the beats or emphasizing them with grouping boundaries, instrumentation, or melodic contours), music with weaker cues may be more ambiguous and can lead to multiple interpretations of the beat” (Iverson and Patel 2014). In other words, by creating strong beat cues, composers can direct their audience’s listening experience, and that in itself can invite various interpretations as one navigates the beats of that work. As seen with both examples, navigation comes across in music composition as a creative practice through the manipulation of techniques such as melodic intervals and beat perceptions.

In conclusion, the exploration of navigation in this essay transcends its conventional boundaries by reaching into the realism of creative humanities and various disciplines. Iris Van Der Tuin and Nanna Verhoeff’s critical concept of navigation serves as a foundation for this multidisciplinary examination. This essay makes connections between navigation and diverse fields such as media studies, literary studies, history, language dynamics, fractal art, cartography practices, and music composition to give a “yes, and” response to the concept provided by the two authors.

By starting with its etymological roots related to seafaring, navigation becomes more evidently clear when deriving further interpretations. Navigation in this current age involves more than just physical movement, it encompasses wayfinding and steering across bodies, perceptions, thoughts, and creative pursuits in various terrains. This essay then moves forward mentioning creative practices, beginning with fractal art, then discussions focusing on decolonization efforts in cartography, projects like the Indigenous Mapping Collective that reclaim indigenous territories and challenge colonial authority through navigation and narration, and music composition.

In essence, this essay seeks to establish that the concept itself can be responded to with a “yes and” statement. Yes, the definition provided by both authors can assuredly be applied to creative practices, and there is room for even more exploration by bringing this concept and projecting it towards the aforementioned disciplines and creative practices to understand what is slightly neglected in the book’s definition itself. The definition provided in the book has a thorough mention of “performative cartography” which infers the idea that navigation in itself is a visual regime, but as been exemplified in each discipline and creative practice, it is not just a visual activity, it is an obscure process that takes place without physical boundaries. Furthermore, as in the case of History, some properties of navigation as defined by Van der Tuin and Verhoeff (2022, 137) may become problematized and find themselves in conflict with the goals of the discipline or field. The process of map-making itself can be extended upon through the introduction of dynamics such as the decolonization effort of the Indigenous Mapping Collective, making it sensitive to cultural changes. Finally, taking as an example current seafaring routes, the generative fields in which navigation takes place present individual and contingent restrictors that may both limit and increase creative agency.

References

Besson, Mireille, and Daniele Schön. 2001. “Comparison between Language and Music.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 930 : 232–58. DOI: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05736.x

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor and John Shawcross. 1907. Biographia Literaria. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Constantine, Roftiel. 2008. GPS and Galileo: Friendly Foes? Air University Press.

Dourish, Paul. 2001. Where the Action Is : The Foundations of Embodied Interaction. Cambridge Mass: MIT Press.

Drucker, Johanna. 2008 “Graphic Devices: Narration and Navigation.” Narrative 16, no. 2: 121–39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30219279.

Genz, Joseph, et al. 2009 “Wave Navigation In The Marshall Islands: Comparing Indigenous And Western Scientific Knowledge Of The Ocean.” Oceanography 22, no. 2: 234–45. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24860973.

Hesketh, Ian. 2014. “The Story of Big History”, History of the Present 4.2 : 171-202. https://doi.org/10.5406/historypresent.4.2.0171.

Horsthuis, Julius. Interview. By Sophie Woodcock. January 5, 2024.

Horsthuis, Maurice. Interview. By Sophie Woodcock. January 5, 2024.

Mandelbrot, Benoit. 1967. “How long is the coast of Britain? Statistical Self-similarity and Fractional Dimension.” SCIENCE 156, no. 3775: 636-638. DOI: 10.1126/science.156.3775.636.

“Indigenous Mapping Collective.” Accessed January 6, 2024. https://www.indigenousmaps.com/ourstory/

Jiang, Bin, and S. Anders Brandt. 2016. “A Fractal Perspective on Scale in Geography.” ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 5, no.95. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1509.08419

Kemp Peter. 1988. The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lei, Tan. (1990).“Similarity between the Mandelbrot Set and Julia Sets.” Communications in Mathematical Physics 134: 587-617. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02098448.

Meyerhoff, Miriam. Introducing sociolinguistics. London: Routledge, 2019.

Olivetti Media Communication – Enrico Olivetti. “Dizionario Latino Olivetti.” Dizionario. Accessed January 13, 2024. https://www.dizionario-latino.com/.

Patel, Aniruddh and John Iverson. 2014. “The Evolutionary Neuroscience of Musical Beat Perception: The Action Simulation for Auditory Prediction (ASAP) Hypothesis.” Front. Syst. Neurosci 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsys.2014.00057.

Lawless, Kimberly A. et al. 2007. “Acquisition of Information Online: Knowledge, Navigation and Learning Outcomes”. Journal of Literacy Research 39(3): 289-306. https://doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1080/10862960701613086.

Philip, Woodcock. Interview. By Sophie Woodcock. December 31, 2023.

Picture 1: https://www.julius-horsthuis.com/showreel

Picture 2: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mandelbrot_set

Picture 3: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coastline_paradox

Rose-Redwood, Reuben, et al. 2020. “Decolonizing the Map: Recentering Indigenous Mappings.” Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization 55(3): 151-162. DOI: 10.3138/cart.53.3.intro.

The Decolonial Atlas. “Home.” Accessed January 6, 2024. https://decolonialatlas.wordpress.com.

Van der Tuin, Iris and Nanna Verhoeff. 2021. Critical Concepts for the Creative Humanities. Blue Ridge Summit: Rowman & Littlefield.